HWR's Occasional Notes to Self

Mittwoch, 24. September 2025

RR Lyrae in the inner Galaxy

Dienstag, 22. Juli 2025

Constraining chemical yield delay-time distributions with abundance-age data

Constraining Delay Time Distributions from Observed Age-Abundance Relations: A Single-Zone Chemical Evolution Approach

Abstract

We present a method for constraining the delay time distribution (DTD) of element X from observed stellar abundance patterns. Using the single-zone chemical evolution framework of Weinberg et al. (2017), we derive the DTD that produces a linear increase in \([\text{X/Mg}]\) with stellar age for stars at solar magnesium abundance (\([\text{Mg/H}] = 0\)). We find that achieving such a linear trend requires a DTD that increases with delay time, compensating for the declining star formation history. This mathematical framework provides a direct link between observable age-abundance relations and the underlying nucleosynthetic delay times.

1. Introduction

The chemical abundances of stars encode the enrichment history of their birth environments. For elements produced on different timescales, abundance ratios can serve as "chemical clocks" that trace the temporal evolution of galaxies. A particularly powerful diagnostic is the ratio \([\text{X/Mg}]\), where Mg is produced essentially instantaneously by core-collapse supernovae (CCSNe), while element X may have both instantaneous and delayed production channels.

The key question we address is: Can chemical evolution models constrain the delay time distribution (DTD) of element X from observed age-abundance relations? Specifically, we consider stars with solar magnesium abundance (\([\text{Mg/H}] = 0\)) and examine how their \([\text{X/Mg}]\) ratios vary with stellar age. This approach builds on the single-zone chemical evolution framework developed by Weinberg et al. (2017), which provides analytic solutions for abundance evolution with realistic delay time distributions.

In this work, we:

- Adapt the Weinberg et al. (2017) framework to the specific case of \([\text{X/Mg}]\) evolution

- Derive the mathematical relationship between observed age-\([\text{X/Mg}]\) trends and the underlying DTD

- Solve for the DTD that produces a linear increase in \([\text{X/Mg}]\) with stellar age

2. Single-Zone Chemical Evolution Framework

2.1 Basic Equations

Following Weinberg et al. (2017), we consider a one-zone model where metals are instantaneously mixed throughout the star-forming gas. The evolution of element masses is governed by:

where:

- \(\dot{M}_*\) is the star formation rate

- \(m^{\text{cc}}_{\text{Mg}}\) and \(m^{\text{cc}}_{\text{X}}\) are the instantaneous yields from CCSNe

- \(m^{\text{delayed}}_{\text{X}}\) is the delayed yield of element X

- \(\eta\) is the outflow mass loading factor

- \(r\) is the recycling fraction

- \(Z_i = M_i/M_g\) is the mass fraction of element \(i\)

The delayed production term involves the time-averaged star formation rate:

where \(f(\tau)\) is the delay time distribution we seek to constrain.

2.2 Solutions for Exponential Star Formation History

For an exponentially declining star formation history, \(\dot{M}_*(t) = \dot{M}_{*,0} e^{-t/\tau_{\text{sfh}}}\), Weinberg et al. (2017) show that the equilibrium abundances are:

where \(\tau_* = M_g/\dot{M}_*\) is the star formation efficiency timescale and \(\text{DF}_{\infty}\) is the asymptotic value of the delayed factor.

2.3 The Delayed Factor

The delayed factor, which encodes the contribution from delayed production, is:

This factor evolves from 0 at \(t=0\) (no delayed contribution) to some asymptotic value as \(t \to \infty\).

3. Connecting Observables to Theory

3.1 The Age-Metallicity Relation

Stars inherit the gas-phase abundances at their formation time. Therefore:

- Old stars (large age \(\tau_{\text{age}}\)) formed at small \(t\) when \([\text{X/Mg}]\) was low

- Young stars (small \(\tau_{\text{age}}\)) formed at large \(t\) when \([\text{X/Mg}]\) was high

The relationship between stellar age and formation time is:

3.2 The [X/Mg] Ratio

The abundance ratio at any time is:

This can be rewritten as:

4. Constraining the DTD from Observations

4.1 The Inverse Problem

Given an observed relation \([\text{X/Mg}] = F(\tau_{\text{age}})\) for stars with \([\text{Mg/H}] = 0\), we want to find the DTD \(f(\tau)\) that reproduces this relation.

For stars with \([\text{Mg/H}] = 0\), we know that:

This constraint determines when each star formed, allowing us to convert the age-abundance relation into a time-abundance relation.

4.2 Linear Age-[X/Mg] Relation

Consider the specific case where \([\text{X/Mg}]\) increases linearly with age:

where \(A\) and \(B\) are constants determined by observations. Converting to formation time:

This requires \([\text{X/Mg}]\) to decrease linearly with formation time.

4.3 Required Delayed Factor Evolution

From the expression for \([\text{X/Mg}]\), we need:

where \(C\) is a constant. Taking the antilog:

Solving for the delayed factor:

5. Deriving the Delay Time Distribution

5.1 The Integral Equation

From the definition of the delayed factor:

Taking the derivative:

Solving for \(f(t)\):

5.2 Solution for Linear [X/Mg] Growth

For the delayed factor derived above:

Substituting into the expression for \(f(t)\):

5.3 Key Mathematical Insight

For typical parameter values where \(B > 0\) (older stars have lower \([\text{X/Mg}]\)):

- The first term dominates and is negative

- This implies \(f(t) < 0\) for some range of \(t\)

- A negative DTD is unphysical!

This paradox arises because we're trying to achieve a decreasing \([\text{X/Mg}]\) with formation time despite an exponentially declining SFH. The resolution requires a modified approach.

6. Physical DTD Solutions

6.1 Compensating for Declining SFH

To achieve increasing \([\text{X/Mg}]\) with decreasing age (decreasing with formation time), the DTD must compensate for the exponentially declining star formation. The required form is:

where \(g(\tau)\) is a normalized distribution. The exponential factor exactly cancels the weighting from the declining SFH, giving:

where \(G(t)\) is the cumulative distribution function of \(g(\tau)\).

6.2 Power-Law Family of Solutions

For a smooth transition from \(\text{DF}(0) = 0\) to \(\text{DF}(t_{\text{max}}) = 1\), consider:

This gives:

The complete DTD is:

6.3 Linear [X/Mg] Growth

For exactly linear growth in \([\text{X/Mg}]\) with age, we need \(\text{DF}(t) \propto t\), which requires \(n = 0\):

This DTD:

- Increases exponentially with delay time

- Peaks at late times

- Provides uniform enrichment rate despite declining SFH

7. Discussion

7.1 Physical Interpretation

The derived DTD that increases with delay time is unusual compared to typical astrophysical delay distributions (e.g., Type Ia SNe, which decline as \(t^{-1.1}\)). Possible physical scenarios include:

- Metallicity-dependent yields: If element X production efficiency increases with metallicity, later generations contribute more

- Multiple sources: A combination of sources with different characteristic timescales

- Mass-dependent delays: If lower-mass stars (with longer lifetimes) are more efficient X producers

7.2 Observational Tests

To apply this framework:

- Measure \([\text{X/Mg}]\) vs age for a sample of stars with \([\text{Mg/H}] \approx 0\)

- Fit the functional form of the age-abundance relation

- Use the derived expressions to constrain the DTD

- Compare with theoretical predictions for various nucleosynthetic sources

7.3 Limitations

This analysis assumes:

- Perfect mixing (one-zone approximation)

- Constant star formation efficiency

- No radial flows or stellar migration

- Metallicity-independent yields

Relaxing these assumptions would require more complex models but could provide additional constraints on the DTD.

8. Conclusions

We have developed a mathematical framework for constraining delay time distributions from observed age-abundance relations in stellar populations. The key findings are:

- Observable \([\text{X/Mg}]\) trends with stellar age directly encode information about the DTD of element X

- For stars at fixed \([\text{Mg/H}]\), the age-abundance relation can be inverted to derive the required DTD

- Achieving a linear increase in \([\text{X/Mg}]\) with age requires a DTD that increases exponentially with delay time

- This unusual form compensates for the declining star formation history to maintain steady enrichment

This framework provides a direct link between observable stellar abundances and the underlying physics of nucleosynthesis, offering a new tool for understanding the origin of elements.

Acknowledgments

We thank...

References

Weinberg, D. H., Andrews, B. H., & Freudenburg, J. 2017, ApJ, 837, 183

Freitag, 14. März 2025

Binary Stars and Gravitational Waves

Gravitational waves (GWs) offer a unique probe into compact binary systems. Non-merging white dwarf (WD) binaries—systems that emit continuous, nearly monochromatic GWs without merging within a Hubble time—are significant sources in the milli-Hertz frequency range, observable by LISA. Here we summarize results for GW strain amplitude from such binaries and details how LISA determines their distance and sky position, with exhaustive derivations and examples.

1. Derivation of the GW Signal

Consider two white dwarfs with masses \( M_1 \) and \( M_2 \), orbiting circularly with period \( P \), at a luminosity distance \( D \) from Earth. We use the quadrupole approximation in the non-relativistic limit to compute the GW strain.

The orbital dynamics are foundational to the GW signal. Define the following:

-

Orbital Angular Frequency (\( \omega \)):

\[ \omega = \frac{2\pi}{P}, \]where \( P \) is the orbital period in seconds, and \( \omega \) is in radians per second. This relates the frequency of rotation to the time for one complete orbit.

-

Total Mass (\( M \)):

\[ M = M_1 + M_2, \]the sum of the individual masses in kilograms, governing the system's gravitational interaction.

-

Reduced Mass (\( \mu \)):

\[ \mu = \frac{M_1 M_2}{M_1 + M_2}, \]a measure of the effective mass for the two-body problem, also in kilograms, which influences the GW amplitude.

-

Orbital Separation (\( a \)): Apply Kepler's third law for a circular orbit:

\[ P = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{a^3}{G M}}, \]where \( G \) is the gravitational constant (\( 6.67430 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{m}^3 \text{kg}^{-1} \text{s}^{-2} \)). Square both sides:\[ P^2 = \frac{4\pi^2 a^3}{G M}. \]Rearrange for \( a^3 \) and take the cube root:\[ a = \left( \frac{G M P^2}{4\pi^2} \right)^{1/3}, \]yielding the semi-major axis \( a \) as function of the period and total mass.

- Orbital Inclination (\( \iota \)): The angle between the orbital angular momentum vector and the line of sight to the observer. For \( \iota = 0 \), the binary is face-on, while for \( \iota = \pi/2 \), it is edge-on.

The GW signal arises from the changing mass quadrupole moment. The orbit lies in a plane that can be tilted with respect to the observer's line of sight. For a general inclination, we first define the positions in the orbital plane and then transform to the observer's frame.

In the orbital plane (with center of mass at the origin), the positions are:

-

WD 1 Position (\( \mathbf{r}_1 \)):

\[ \mathbf{r}_1 = \left( \frac{M_2}{M} a \cos \omega t, \frac{M_2}{M} a \sin \omega t, 0 \right), \]where \( \frac{M_2}{M} a \) is the distance from the center of mass to WD 1.

-

WD 2 Position (\( \mathbf{r}_2 \)):

\[ \mathbf{r}_2 = \left( -\frac{M_1}{M} a \cos \omega t, -\frac{M_1}{M} a \sin \omega t, 0 \right), \]with \( \frac{M_1}{M} a \) as the distance to WD 2, and the negative sign ensuring the center of mass condition \( M_1 \mathbf{r}_1 + M_2 \mathbf{r}_2 = 0 \).

The mass quadrupole tensor is:

where \( \delta_{ij} \) is the Kronecker delta, and \( r_k^2 = (r_k^x)^2 + (r_k^y)^2 + (r_k^z)^2 \). Compute key components:

-

\( I_{xx} \):

\[ I_{xx} = M_1 \left( \frac{M_2}{M} a \cos \omega t \right)^2 + M_2 \left( -\frac{M_1}{M} a \cos \omega t \right)^2, \]\[ = M_1 \frac{M_2^2 a^2 \cos^2 \omega t}{M^2} + M_2 \frac{M_1^2 a^2 \cos^2 \omega t}{M^2}, \]\[ = \frac{M_1 M_2^2 + M_2 M_1^2}{M^2} a^2 \cos^2 \omega t = \frac{M_1 M_2 (M_1 + M_2)}{M^2} a^2 \cos^2 \omega t, \]\[ = \mu a^2 \cos^2 \omega t. \]Adjust for the trace:\[ r_1^2 = \left( \frac{M_2}{M} a \right)^2 (\cos^2 \omega t + \sin^2 \omega t) = \left( \frac{M_2}{M} a \right)^2, \]\[ I_{xx} = \mu a^2 \cos^2 \omega t - \frac{1}{3} \mu a^2 \delta_{xx} = \mu a^2 \left( \cos^2 \omega t - \frac{1}{3} \right). \]

-

\( I_{yy} \):

\[ I_{yy} = \mu a^2 \sin^2 \omega t - \frac{1}{3} \mu a^2 = \mu a^2 \left( \sin^2 \omega t - \frac{1}{3} \right). \]

-

\( I_{xy} = I_{yx} \):

\[ I_{xy} = M_1 \left( \frac{M_2}{M} a \cos \omega t \right) \left( \frac{M_2}{M} a \sin \omega t \right) + M_2 \left( -\frac{M_1}{M} a \cos \omega t \right) \left( -\frac{M_1}{M} a \sin \omega t \right), \]\[ = \mu a^2 \cos \omega t \sin \omega t. \]

GWs depend on the second time derivative \( \ddot{I}_{ij} \):

-

\( \ddot{I}_{xx} \):

\[ \dot{I}_{xx} = \mu a^2 \frac{d}{dt} (\cos^2 \omega t) = \mu a^2 \cdot 2 \cos \omega t (-\omega \sin \omega t) = -2 \mu a^2 \omega \cos \omega t \sin \omega t, \]\[ \ddot{I}_{xx} = \frac{d}{dt} (-2 \mu a^2 \omega \cos \omega t \sin \omega t), \]\[ = -2 \mu a^2 \omega \left[ (-\omega \sin \omega t) \sin \omega t + \cos \omega t (\omega \cos \omega t) \right], \]\[ = -2 \mu a^2 \omega^2 (-\sin^2 \omega t + \cos^2 \omega t) = -2 \mu a^2 \omega^2 \cos 2\omega t, \]using the identity \( \cos^2 \omega t - \sin^2 \omega t = \cos 2\omega t \).

-

\( \ddot{I}_{yy} \):

\[ \ddot{I}_{yy} = -\ddot{I}_{xx} = 2 \mu a^2 \omega^2 \cos 2\omega t, \]

-

\( \ddot{I}_{xy} \):

\[ \dot{I}_{xy} = \mu a^2 \frac{d}{dt} (\cos \omega t \sin \omega t) = \mu a^2 \left[ (-\omega \sin \omega t) \sin \omega t + \cos \omega t (\omega \cos \omega t) \right], \]\[ = \mu a^2 \omega (\cos^2 \omega t - \sin^2 \omega t) = \mu a^2 \omega \cos 2\omega t, \]\[ \ddot{I}_{xy} = \mu a^2 \omega \frac{d}{dt}(\cos 2\omega t) = \mu a^2 \omega (-2\omega \sin 2\omega t) = -2 \mu a^2 \omega^2 \sin 2\omega t. \]

In the transverse-traceless (TT) gauge, the GW strain for an observer at inclination \( \iota \) is:

where \( c \) is the speed of light (\( 3 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s} \)), and \( D \) is in meters.

When accounting for inclination \( \iota \), we need to project the quadrupole tensor onto the observer's reference frame. For an observer along a general direction, the two polarization components become:

The overall GW strain amplitude scales as:

Substitute \( a \) and \( \omega \):

Simplify:

Relate to GW frequency \( f = \frac{2}{P} \) (since GWs oscillate at twice the orbital frequency), so \( P = \frac{2}{f} \):

Introducing the chirp mass:

the strain can be written in the standard form:

where \( \mathcal{A}(\iota) = \sqrt{(1 + \cos^2 \iota)^2 + 4\cos^2 \iota}/4 \) is the inclination-dependent amplitude factor.

While many WD binaries can be treated as monochromatic sources, some systems evolve measurably during observation. The orbital decay due to gravitational wave emission causes the frequency to increase over time, producing a "chirping" signal.

The energy loss due to gravitational wave emission is given by:

The orbital energy can be related to frequency:

Taking the time derivative and equating with the energy loss rate:

Solving for \(\dot{f}_{\text{orb}}\):

For gravitational waves with \(f_{GW} = 2f_{orb}\):

This frequency derivative is a strong function of both frequency and chirp mass, making it potentially detectable for higher frequency systems with larger masses.

The time-dependent GW polarizations for a binary with inclination \( \iota \) are:

where \( h_0 \) is the overall amplitude and \( \phi_0 \) is an initial phase. Note that for chirping sources, we've included the $\pi\dot{f}t^2$ phase term.

For different inclinations:

-

Face-on (\( \iota = 0 \)):

\[ h_+ = h_0 \cos(2\pi f t + \pi\dot{f}t^2 + \phi_0), \quad h_{\times} = h_0 \sin(2\pi f t + \pi\dot{f}t^2 + \phi_0) \]The GW has equal plus and cross polarizations, 90° out of phase, creating circular polarization.

-

Edge-on (\( \iota = \pi/2 \)):

\[ h_+ = \frac{h_0}{2} \cos(2\pi f t + \pi\dot{f}t^2 + \phi_0), \quad h_{\times} = 0 \]Only the plus polarization remains, creating linear polarization with reduced amplitude.

2. Extracting Distance and Position with LISA

LISA, with its \( a \approx 2.5 \times 10^9 \, \text{m} \) baseline, uses the GW signal to infer \( D \), sky position \( (\alpha, \delta) \), and inclination \( \iota \).

From:

LISA measures \( h_+ \) and \( h_{\times} \) separately, allowing determination of both \( D \) and \( \iota \) through:

which gives \( \iota \), and then:

Note that for purely monochromatic sources, $M_{\text{chirp}}$ remains degenerate with distance, and may require electromagnetic counterparts or statistical priors to determine independently.

For binaries where LISA can measure \(\dot{f}_{GW}\), the chirp mass can be determined independently:

This breaks the degeneracy between chirp mass and distance, allowing for direct distance determination:

LISA can typically detect frequency evolution when:

- The frequency shift over the observation period is larger than the Fourier bin width: $\dot{f}_{GW} \cdot T_{obs}^2 > 1$

- The signal-to-noise ratio is sufficient (typically SNR $\gtrsim$ 20)

- The binary has higher frequency ($f_{GW} \gtrsim 3$ mHz) and/or larger chirp mass

The precision in distance determination improves dramatically when $\dot{f}_{GW}$ is measurable:

For typical WD binaries at mHz frequencies with 4-year observation times, distance precision can improve from factors of many tens of percent to approximately 10-30% when $\dot{f}_{GW}$ is detectable.

LISA leverages several effects for sky localization:

-

Doppler Modulation:

\[ f_{\text{obs}} = f \left(1 + \frac{\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n}}{c} \right), \]where \( \mathbf{v} \) is LISA's orbital velocity (~30 km/s around the Sun), and \( \mathbf{n} \) is the unit vector to the source, modulating \( f \) over its 1-year orbit.

-

Amplitude Modulation:

\[ h(t) = F_+ h_+ + F_{\times} h_{\times}, \]where \( F_+, F_{\times} \) are antenna pattern functions depending on \( (\alpha, \delta) \) and LISA's orientation.

-

Sky Localization Area:

For short observations, the resolution is limited by the detector arm length \( a \):

\[ \Delta \Omega_{\text{short}} \sim \frac{1}{\text{SNR}^2} \left( \frac{\lambda}{a} \right)^2, \quad \lambda = \frac{c}{f}, \]But for long-term observations (≈1 year), LISA's orbital motion provides an effective baseline of \( 2 R_{\text{orbit}} \) (≈ 2 AU):\[ \Delta \Omega_{\text{long}} \sim \frac{1}{\text{SNR}^2} \left( \frac{\lambda}{2 R_{\text{orbit}}} \right)^2 \]where SNR is the signal-to-noise ratio, and \( \lambda \) is the GW wavelength.

For \( f = 1 \, \text{mHz} \) and short-term observations with LISA's arm length \( a \approx 2.5 \times 10^9 \, \text{m} \):

Sonntag, 2. Juni 2024

Possible Masters Projects

Project 1:

The Dynamical Structure and Population of the Extremely Metal-Rich "Knot" at the center of the Milky Way

Background

|

| All-sky maps of the stellar density for very metal-rich stars in the inner Galaxy (from Rix+2024). Note that the extremely metal-rich stars (EMR; bottom panel) are largely confined to a central "knot". |

- did the stars form there?

- on what orbits are they? radial, rotating, etc..

- how old are they? (did they form in several episodes)

Goal

(possible) steps

- collect all data (velocities, metallicities) of existing and new SDSS/APOGEE spectra in the inner 1.5 kpc of the Milky Way

- find the very metal rich ones

- get the best possible distances of these stars (Gaia and spectroscopic information)

- combine SDSS/APOGEE information with Gaia to determine orbits

- determine orbit distribution, mostly the distribution in binding energy (or apocenter) and eccentricity.

- build a simple dynamical model.

- determine the spatial and orbit distribution, and (optional) compare it to TNG50 Milky Way formation simulations.

Tools

- working with the sloan data base

- working with python dynamics packages such as galpy

- writing a set of jupyter notebooks (or other forms of python code) to do further analysis and make plots.

Hoped-For Outcome

Project 2:

Mapping the Metallicity of Young Stars across the Milky Way Disk

Background

What to take for young luminous stars: the easiest would be to take hot young stars (OB stars); but they have few metal lines, so it is hard to measure [Fe/H]. But all stars (>Mio years) have a red giant phase, where they are cool enough to yield metallicities.

Goal

|

| CMD positions of red giants with solar metallicity, but different ages |

|

| CMD positions of stars of 10^9 years age, but of different metallicities. Age and metallicity are covariant. |

Goal (possible) steps

- take intellectual ownership of the age fitting code (with some possible tweaks/checks)

- collect the data (from Gaia; catalogs exist) of the stellar parameters for all "Gaia giants with spectroscopy". find the subset with good distances, and apply age-fitting code.

- find the young giants

- make metallicity maps

- take it from there..

Tools

- working with Gaia and zenodo data base

- learn and adopt a piece of existing code

- writing a set of jupyter notebooks (or other forms of python code) to do further analysis and make plots.

- working with Gaia and zenodo data base

- learn and adopt a piece of existing code

- writing a set of jupyter notebooks (or other forms of python code) to do further analysis and make plots.

Hoped-For Outcome

Leading a refereed population on this analysis

Montag, 5. Februar 2024

Thoughts on Wide-Field Slitless Spectroscopy from Space

Slit-less Survey Spectroscopy from Space

- let's presume a 6.5m (warm?) telescope could be designed [credit to Roger Angel here] with a near diffraction limited 0.25 (or 1) sqdeg FOV in a TESS-like or L2 orbit ;

- and if one could then implement slitless spectroscopy with a resolution R (say R=1000, or 2000?), and a bandpass filter that picks out NR (say NR=1000, or 2000?) resolution elements

- the actual wavelength requires a great deal of thought, but let's take here 0.8mum-1.6mum

- Notes:

- a 1sqdeg FOV would require about 20 Gpixels (same as imaging at the same resolution and FOV); so, thinking about undersampling, or 0.25sqdeg may make this idea less pie-in-the-sky

- note that the number of pixels needed is the same as for direct imaging; it's just imaging with every source being a short streak

- How long is the slitless spectral streak in the focal plane? for NR resolution elements, the streak is NR * FWHM(PSF) = 47" at NR=1000; lambda=1.5mum, D=6.5m

- then obvious science include (see section below the S/N estimates for more/growing detail). Brief quip: that MSE, SpecTel, Roman, etc.. just much better.

- stellar physics

- Galactic history, structure and dynamics

- redshift surveys

- AGN finding

- good angular resolution

- spectral "follow-up" on LISA GW sources

- to cover a good portion of the sky "in a reasonable period" (few years?), exposure times per pointing 1000s-ish?

Here are some plots that show an initial S/N estimate exercise. Given that the background tends to kill you in slitless spectroscopy, compact sources (PSF) are great.

Science Cases with such a Survey:

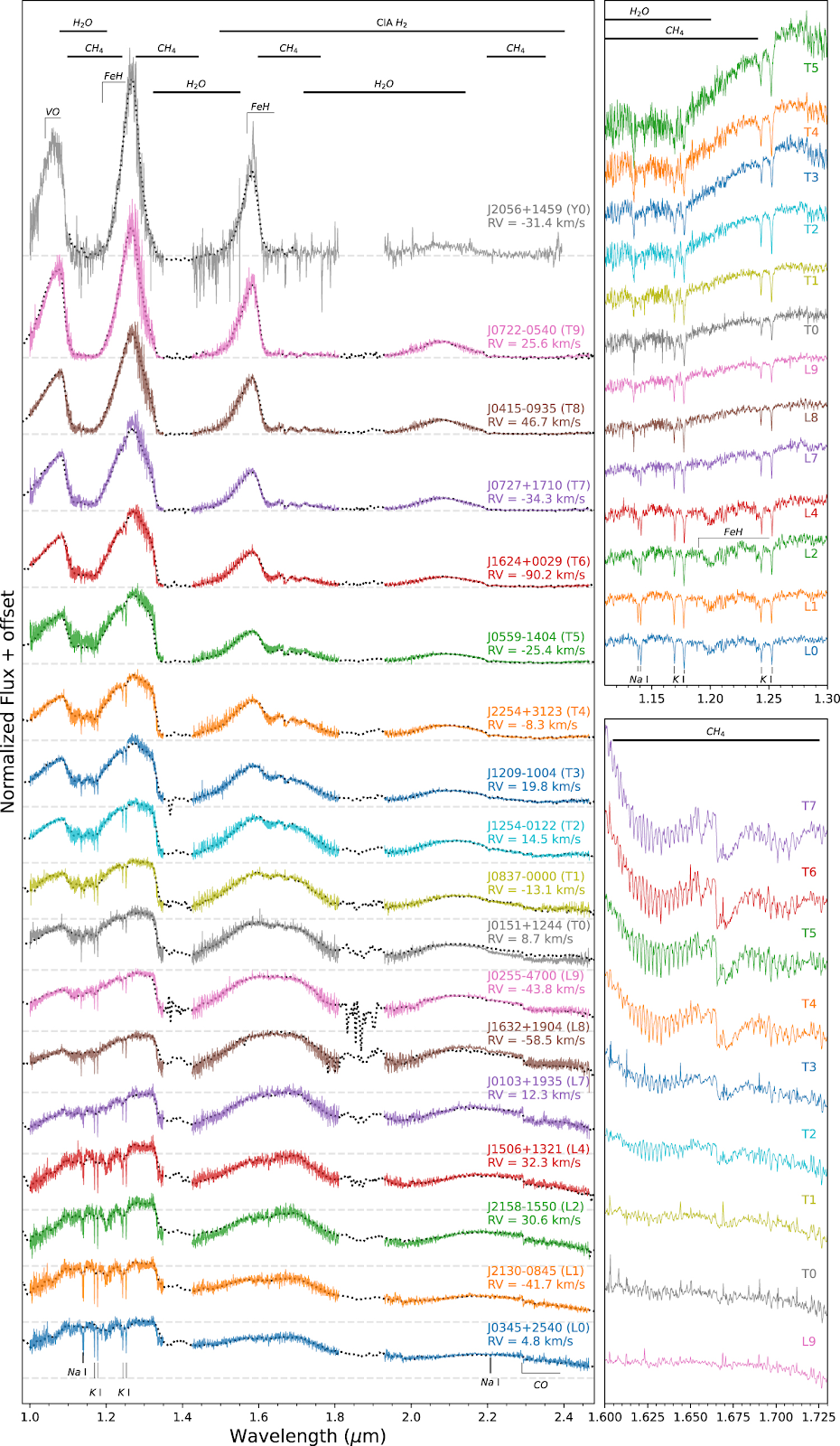

Spectra of Stars:

- 2-5 abundances of cool stars

- are there any zero-metallicity stars in the Milky Way?

- chemical identification of streams (as small-scale DM probes)

- find the fastest stars (in the bulge): BH dynamics

- spectra of every O stars within 5 Mpc

- free-floating (semi-young) planets and stuff

Spectra of AGNs:

- AGN as LSS probes to z=7(?)

- earliest AGN (z~12) ==> BH growth; seed BHs

Spectra of Galaxies

- ?? <what are the most interesting things>

- host galaxy diagnostics of BH GW events with LISA

Cosmology:

(inadvertent) Spectra of Transients

- way too many gravitational lenses with spectra

- serendipidous (single epoch) SN spectra to faint levels

- GRB hosts

- tidal disruption events in AGN

- <you name it>

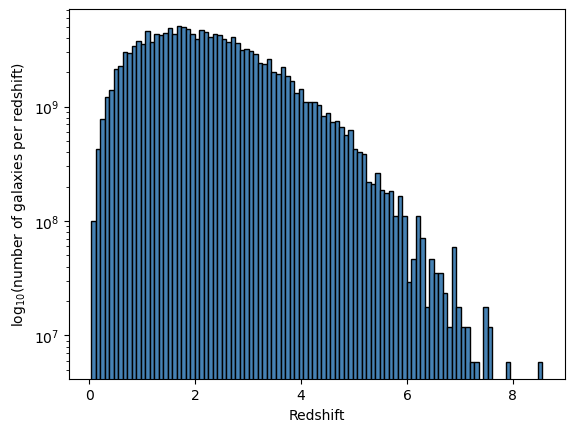

Low-mass objects

- there are ATMO2020 models from Phillips+2020 and newer (JWST-oriented) models Legget&Tremblin 2024

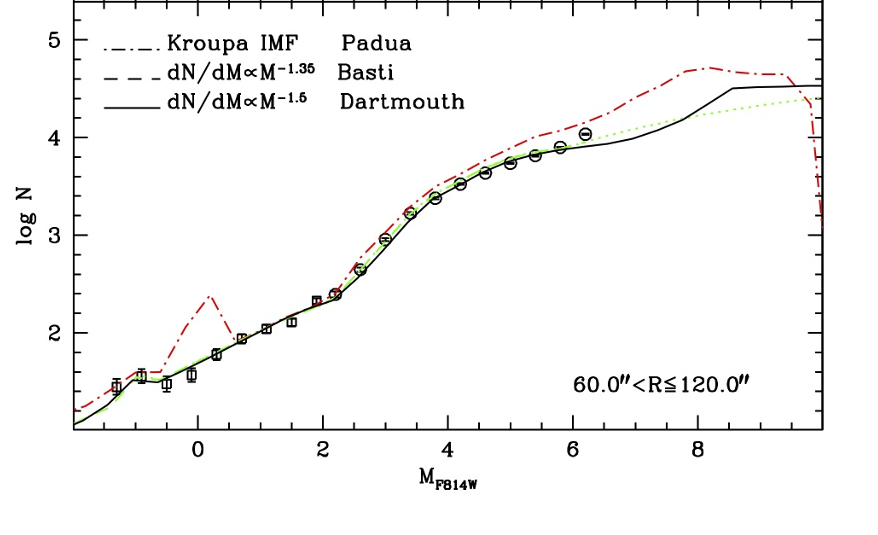

(from Bellazini+ https://arxiv.org/abs/1203.3024)

Notes on crowding:

More science application ideas

The universe through a looking-glass

So, there is a 1 in a million chance to get magnification of more than a 1000. A linear magnification of 20 leads to a physical resolution (6.5m at 0.75mum) of 9 pc at z=5.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)