Kinematic Weak Lensing with Spatially Unresolved Line Widths

Executive Summary

This project articulates a formalism for kinematic lensing using spatially unresolved line widths (HI 21cm or optical) combined with imaging survey ellipticities, building on Huong et al 2025. The Tully-Fisher relation constrains a disk galaxy's inclination, which determines the magnitude $|\varepsilon_{\rm incl}|$ of its intrinsic ellipticity but not its orientation $\phi_n$. This constrains the gravitational shear $\gamma$ to lie on a ring of radius $R$ in the $(\gamma_1, \gamma_2)$ plane, partially breaking the shape-noise degeneracy.

In particular we incorporate that the information content depends on the ratio $R/\sigma_m$: face-on galaxies ($R \ll \sigma_m$) provide full two-dimensional constraints with no information loss, while only edge-on galaxies suffer the factor-of-4 reduction in power found in variance-based treatments. Since face-on and moderately inclined systems contribute ~95% of the Fisher information, we find gain factors $G \approx 3$ over standard weak lensing for realistic DSA-2000 + Euclid/Roman parameters—corresponding to factor of $\approx 3$ reduction in required sample size for a given shear precision.

Context and Goals

The Shape Noise Problem

Weak gravitational lensing measures the coherent distortion of background galaxy shapes by foreground mass concentrations. The cosmological shear signal is small ($|\gamma| \sim 0.01$–$0.03$), while galaxies have intrinsic ellipticities with dispersion $\sigma_{\rm int} \approx 0.25$–$0.3$ per component. This shape noise is the dominant source of statistical uncertainty in current and future surveys. Precision scales as $\sigma_\gamma \propto \sigma_{\rm int}/\sqrt{N}$, requiring very large samples.

The Kinematic Lensing Idea

If we knew each galaxy's intrinsic ellipticity $\varepsilon_{\rm src}$, we could measure shear directly: $\gamma = \varepsilon_{\rm obs} - \varepsilon_{\rm src}$. For disk galaxies, the intrinsic ellipticity is set by the viewing geometry—specifically the inclination angle $i$. An independent measurement of $i$ (e.g., from the Tully-Fisher relation) partially breaks the shape noise degeneracy.

Two regimes exist:

- Resolved kinematics: Spatially resolved velocity fields (IFU spectroscopy) determine both inclination $i$ and position angle $\phi_n$, fully specifying $\varepsilon_{\rm src}$. Limited to bright, nearby galaxies.

- Unresolved line widths: Integrated HI 21cm profiles constrain $\sin i$ via Tully-Fisher, giving $|\varepsilon_{\rm incl}|$ but not $\phi_n$. Applicable to tens of millions of galaxies with forthcoming radio surveys.

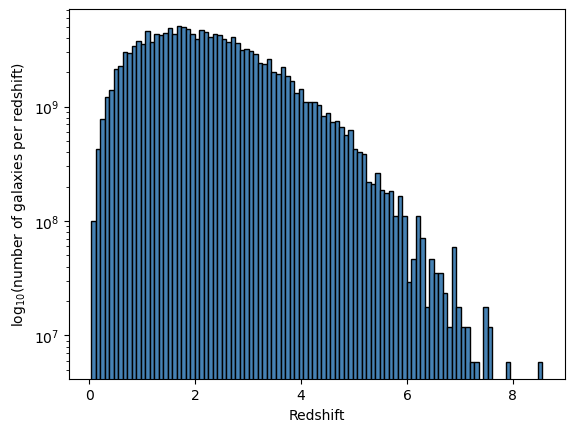

The Opportunity: DSA-2000 + Euclid/Roman

The Deep Synoptic Array (DSA-2000) will detect HI 21cm emission from $>3 \times 10^7$ galaxies over $\sim$30,000 deg², with substantial overlap with Euclid ($\sim$15,000 deg²) and Roman imaging. This creates an unprecedented opportunity:

- Euclid/Roman provide precise shape measurements ($\sigma_m \sim 0.15$–$0.25$) and stellar masses $M_\star$ for Tully-Fisher calibration

- DSA-2000 provides HI line widths (inclination constraints) and precise spectroscopic redshifts

- Combined: Kinematic lensing with $>10^7$ galaxies, independent systematics from radio vs. optical

Goals of This Work

- Develop the likelihood formalism for shear inference from the ring constraint, going beyond variance-based approximations

- Quantify the information content as a function of inclination, revealing which galaxies contribute most

- Calculate realistic gain factors $G$ over standard weak lensing, including finite disk thickness and non-axisymmetry

- Compare with existing work (Huang et al. 2025) and clarify what is new

- Provide a foundation for optimal shear estimation pipelines combining radio and optical data

Core Formalism

Ellipticity and Shear

We adopt the standard weak lensing convention for complex ellipticity. For axis ratio $q \leq 1$ and position angle $\phi$:

In the weak lensing regime, the observed ellipticity relates to source ellipticity and shear by:

where $\eta$ represents measurement noise with variance $\sigma_m^2$.

Inclination from Tully-Fisher

For a thin axisymmetric disk at inclination $i$, the intrinsic ellipticity is:

The Tully-Fisher relation constrains $\sin i$ via the observed HI line width:

with intrinsic scatter $\sigma_{\rm TF}$ propagating to fractional uncertainty $\sigma_f$ on $\sin i$.

The Ring Constraint

Combining these relations, the shear is:

Since $\phi_n$ is unknown (uniformly distributed on $[0,\pi)$ for unresolved observations), the shear is constrained to a circle:

with center at $\varepsilon_{\rm obs}$ and radius $R = |\varepsilon_{\rm incl}|$ determined from the line width.

The Ring Likelihood

Single Galaxy

The likelihood for shear $\gamma$ given observed ellipticity and ring radius is obtained by marginalizing over $\phi_n$:

Defining $d \equiv |\varepsilon_{\rm obs} - \gamma|$ and evaluating the integral yields the Bessel likelihood:

where $I_0$ is the modified Bessel function of the first kind. This likelihood is not Gaussian—it is ring-shaped, peaked at $d = R$.

Limiting Regimes

Face-on limit ($R \ll \sigma_m$): Using $I_0(x) \approx 1$ for small $x$:

This is a standard 2D Gaussian—the ring degenerates to a point.

Edge-on limit ($R \gg \sigma_m$): Using $I_0(x) \approx e^x/\sqrt{2\pi x}$ for large $x$:

The likelihood is sharply peaked on the ring $d = R$, constraining only the radial direction.

Including Tully-Fisher Uncertainty

The TF scatter $\sigma_f$ propagates to uncertainty on $R$:

Through the chain $\sin i \to \cos i \to R$:

This diverges for edge-on galaxies ($\cos i \to 0$), explaining their negligible information contribution.

The total radial uncertainty combines measurement noise and TF scatter:

Combined Likelihood for Multiple Galaxies

For $N$ galaxies in a local region probing a common shear $\gamma$:

This is a sum of "ring potentials"—the maximum likelihood $\hat{\gamma}$ occurs where the rings best intersect.

Fisher Information

The Rank-1 Structure

In the sharp-ring limit, the Fisher matrix for a single galaxy is rank-1:

This constrains only the radial direction; the tangential direction (along the ring) is unconstrained.

The $n_{\rm eff}$ Formula

The Fisher information per galaxy depends on $R/\sigma_m$, interpolating between face-on and edge-on limits:

$n_{\rm eff} = 2$

$F = 1/(\sigma_m^2 + \sigma_R^2)$

Full 2D information

$n_{\rm eff} \to 1$

$F = 1/[2(\sigma_m^2 + \sigma_R^2)]$

Rank-1 (factor of 2 in Fisher)

Combining $N$ Galaxies

For random orientations $\{\phi_{n,i}\}$, the averaged Fisher matrix becomes diagonal:

Individual rank-1 constraints sum to full-rank when galaxies have diverse $\phi_n$.

Standard Weak Lensing Comparison

Without kinematic information, the intrinsic ellipticity is unknown with population variance $\sigma_{\rm int}^2$:

The Gain Factor

For an isotropic inclination distribution ($\cos i$ uniform on $[0,1]$), the population average becomes:

where $x = \cos i$, $R(x) = (1-x)/(1+x)$, and $\sigma_R(x) = 2R(1+R)/(1-R) \cdot \sigma_f \sqrt{1-x^2}/x$.

Realistic Disk Properties

Finite Thickness

Real disks have intrinsic thickness $q_0 \sim 0.2$. The observed axis ratio becomes:

modifying the ellipticity–inclination relation:

Key effects: $R_{\rm max} \approx 0.67$ for $q_0 = 0.2$ (not 1.0); face-on disks have $R_{\rm min} \approx 0.09$ (not 0).

Non-Axisymmetry

Bars, spirals, and warps add ellipticity not captured by the inclination model:

with $\sigma_{\rm disk} \sim 0.05$ from empirical constraints.

Numerical Results

Gain Factors — Idealized Thin Disks

| $\sigma_f$ | $\sigma_m = 0.10$ | $\sigma_m = 0.15$ | $\sigma_m = 0.20$ | $\sigma_m = 0.25$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 14.6 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 3.4 |

| 0.05 | 8.5 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| 0.10 | 7.4 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| 0.15 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 2.3 |

| 0.20 | 6.2 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 2.2 |

Highlighted: DSA-2000 realistic range ($\sigma_f \approx 0.10$–$0.15$)

Gain Factors — Realistic Disks ($q_0=0.2$, $\sigma_{\rm disk}=0.05$)

| $\sigma_f$ | $\sigma_m = 0.10$ | $\sigma_m = 0.15$ | $\sigma_m = 0.20$ | $\sigma_m = 0.25$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 8.0 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| 0.05 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| 0.10 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| 0.15 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| 0.20 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

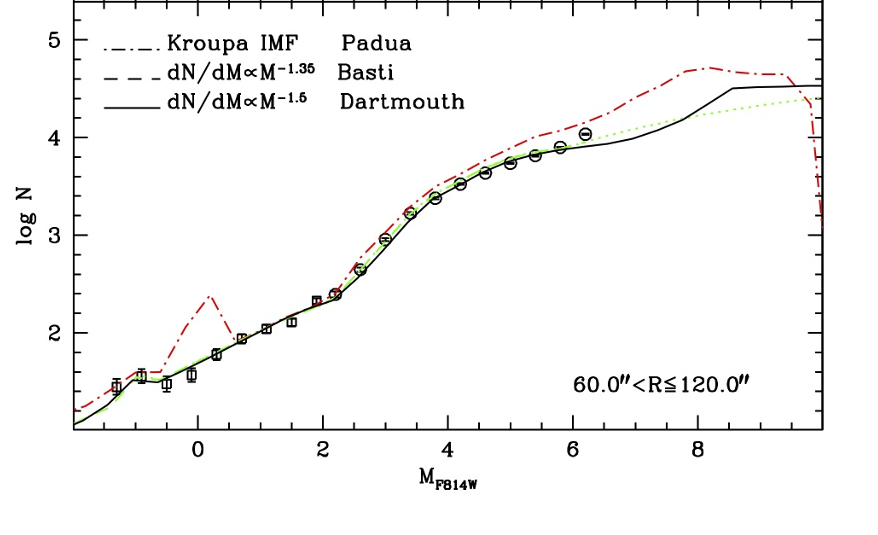

Information Budget by Inclination

For $\sigma_m = 0.2$, $\sigma_f = 0.1$ (thin disk):

| Inclination Range | Fraction of Total Information |

|---|---|

| Face-on ($i < 26°$) | 25% |

| Low inclination ($26° < i < 46°$) | 44% |

| Moderate ($46° < i < 60°$) | 26% |

| High inclination ($60° < i < 73°$) | 5% |

| Edge-on ($i > 73°$) | <1% |

Comparison with Huang, Krause et al. (2025)

Reference: arXiv:2510.18011

| Aspect | Huang et al. | This Work |

|---|---|---|

| Basic constraint | $\gamma = \varepsilon_{\rm obs} - |\varepsilon_{\rm incl}|e^{2i\phi}$ Same | Identical equation |

| Methodology | Correlation functions $\xi_\pm$ | Per-galaxy Bessel likelihood New |

| Information loss | Uniform factor-of-4 in $C_\ell$ | $R$-dependent $n_{\rm eff}$ New |

| Face-on galaxies | Same penalty as edge-on | Full 2D, no penalty New |

| Galaxy weighting | Uniform | Optimal: $\propto n_{\rm eff}/\sigma_{\rm rad}^2$ New |

File Inventory

LaTeX Paper

kinematic_lensing_paper_v2.tex— Main paper (13 pages)kinematic_lensing_paper_v2.pdf— Compiled PDF

Figures

figure1_ring_constraint.png/pdf— Ring geometry schematicfigure2_gain_factor_v2.png/pdf— $G$ vs $\sigma_f$

Code & Documentation

kinematic_lensing_figures_v2.ipynb— Figure generation notebookCLAUDE.md— Context file for Claude Code

Fiducial Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shape measurement noise | $\sigma_m$ | 0.15–0.25 | Euclid/Roman |

| TF fractional scatter | $\sigma_f$ | 0.10–0.15 | HI surveys |

| Disk thickness | $q_0$ | 0.15–0.25 | Observations |

| Non-axisymmetry | $\sigma_{\rm disk}$ | 0.03–0.07 | Bars/spirals |

| Galaxy count | $N$ | $>10^7$ | DSA-2000 |

| Sky overlap | — | ~15,000 deg² | Euclid $\cap$ DSA |

Future Directions

Theory

- Full likelihood MCMC shear inference

- Modified $\xi_\pm$ with $n_{\rm eff}$ weighting

- Intrinsic alignment mitigation

- TF evolution $\sigma_f(z)$

Applications

- DSA-2000 detailed forecasts

- SKA comparison

- Optical emission lines (H$\alpha$, [OII])

- Cosmological parameter forecasts

Key References

- Huang et al. (2025), arXiv:2510.18011 — One-component KL, SKA2 forecasts

- Huff et al. (2013), MNRAS 431, 1629 — "Kinematic lensing" terminology

- Blain (2002), ApJ 570, L51 — First KL proposal

- Gurri et al. (2020), MNRAS 499, 4591 — First KL measurement

- Hallinan et al. (2019), BAAS 51, 255 — DSA-2000